Media Release: Nelson, New Zealand – 10 July 2024 – Kimer Med $10M closer to…

A new virus has recently been discovered in China. Should we be alarmed?

An international team of scientists is now monitoring a newly-identified and potentially dangerous virus that is believed to have ‘jumped’ from animals to humans. You may recall that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, spilled over from bats into the human population, and how that has not been great for us humans.

The new virus, thought to be carried by shrews (small, insect-eating mammals), is known as Langya henipavirus – AKA “Langya” or “LayV”. It was first identified in 2018 when a farmer was treated for a fever at a hospital in the northeastern Chinese province of Shandong. Follow-up investigations were carried out between 2018 and 2021, and these revealed 34 more cases spread throughout the same area, and in the neighbouring province of Henan, mostly among other farmers. So far there have been no reports of human to human transmission, but this possibility has not been ruled out.

To date, the symptoms of Langya infection appear to be relatively mild and similar to many other viral infections – headache, fever, cough, fatigue, loss of appetite, vomiting and muscle aches. However, several patients have also developed signs of kidney and liver damage, which is more concerning, although no deaths have been reported.

The very real threat of zoonotic spillover

The discovery of Langya can be seen as a further warning of the ongoing threat of viral diseases that are currently circulating in animal populations and have the potential to infect humans. When a virus crosses from animals to humans, it’s known as ‘zoonotic spillover’. Viruses aren’t the only pathogens to do this – fungi, bacteria and parasites can all make the leap from an animal to a human host as well.

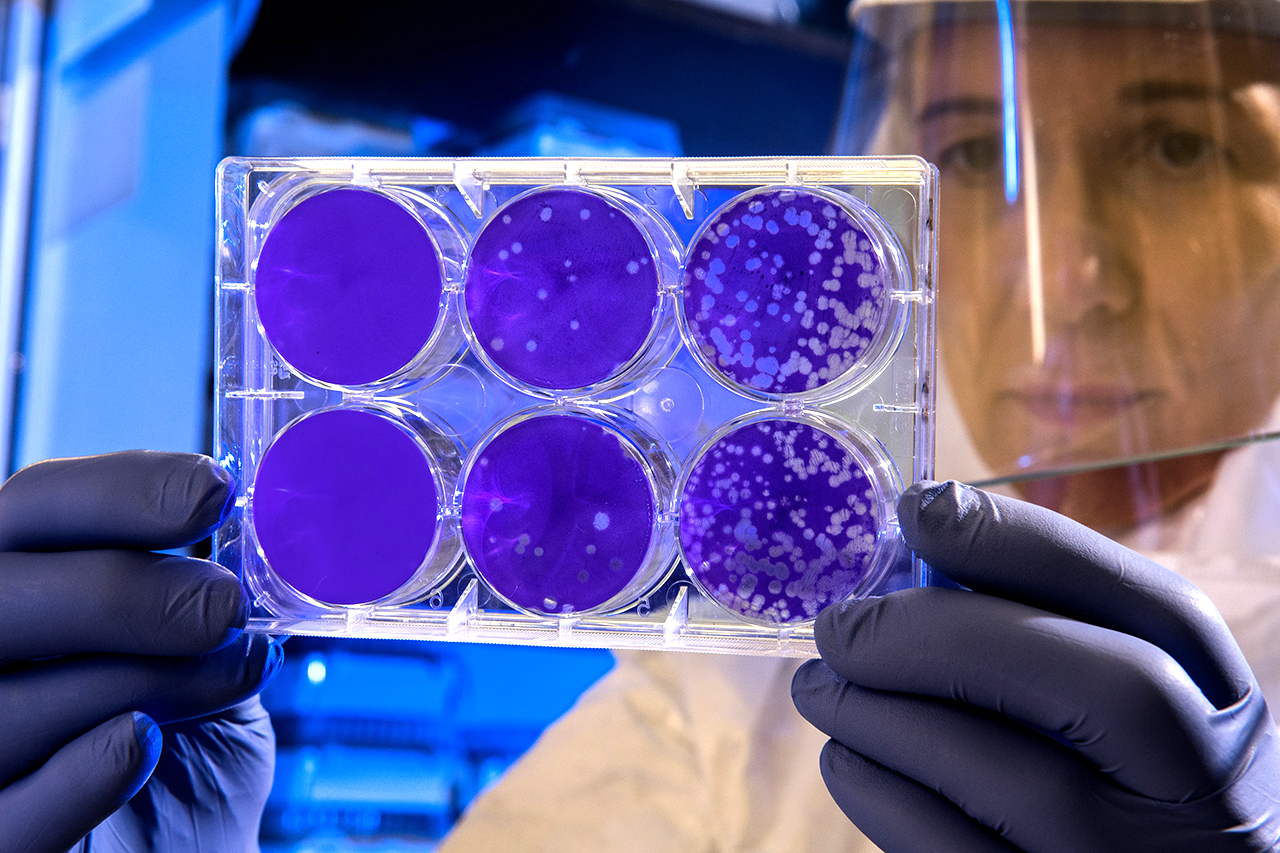

For a virus to ‘spillover’ from one species to another, it has to overcome a few barriers. These include finding a way to unlock receptors on the new host’s cell surfaces and then figuring out how to start replicating in those cells without drawing attention to itself and alerting the host’s immune system. There is ongoing work by scientists to understand the molecular process that viruses use to overcome these barriers, and it’s hoped that this will help identify the viruses that are most likely to trigger a new outbreak, before it occurs.

The deadly henipavirus family

In the case of Langya we can be grateful that so far it does not appear to be the start of another global pandemic. But just how concerned about its emergence should we be? Well, the answer is at least “moderately”, because Langya belongs to the henipavirus family, which is the same family as the deadly Nipah and Hendra viruses.

Nipah virus can be transmitted to humans from animals, and from human to human. Infection in humans can cause acute respiratory infection and fatal encephalitis (inflammation of the brain), and has a case fatality rate of between 40% to 75%. In case it’s not obvious, that means if 100 people are infected with the virus, between 40 and 75 of them will die!

Although rare, Hendra virus is equally nasty, with an estimated case fatality rate of 57%. Hendra is carried by bats and causes severe and often fatal disease in both infected horses and humans. It’s named after a suburb in Brisbane, Australia, where an outbreak of the virus in horses was first recorded in 1994.

Currently there is no approved vaccine against any of the henipaviruses for humans. There is also no antiviral – so treatment tends to consist only of supportive care and the easing of symptoms.

Climate change, urbanisation and deforestation is driving more viral spillovers

Scientists who study zoonotic diseases warn that spillover events like the case of Langya, and the bat-to-human transmission that led to the COVID-19 pandemic, will only become more and more common. The finger of blame for this is pointed at deforestation, urbanisation and the shrinking of natural animal habitats due to climate change – leading to more and closer interactions between humans and disease-carrying animals. Alarmingly, it is estimated that there are as many as 500,000 more viruses that have the potential to spillover from animals to humans!

Please share and help us spread the word

At Kimer Med we are continuing our work to develop a broad-spectrum antiviral treatment against this existential threat. There are some simple ways you can help us win the fight against deadly viral disease: share this post, spread the word about our work, donate to support our work, and partner with us for research and testing of our antiviral compound. Thank you.

References:

https://www.livescience.com/china-detects-new-langyu-virus

https://cen.acs.org/biological-chemistry/infectious-disease/How-do-viruses-leap-from-animals-to-people-and-spark-pandemics/98/i33#:~:text=The%20Bombali%20virus%20highlights%20an,the%20time%2C%E2%80%9D%20Goldstein%20says

https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/basics/zoonotic-diseases.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Langya_henipavirus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hendra_virus

https://www.who.int/health-topics/hendra-virus-disease#tab=tab_1

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/nipah-virus

https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2020/travel-related-infectious-diseases/henipaviruses#:~:text=TREATMENT,proposed%20for%20Hendra%20in%20Australia.